The art and power of film is hugely important to us at Wonderhatch – we’re a team of filmmakers and film lovers, and you only need to look as far as our recent work for BFI’s London Film Festival to see that. Recently, our co-founder Marc Webbon was asked to speak at the American Society of Architectural Illustrators on the power of filmmaking in shaping the future skyline. So what exactly does film has to do with architecture and building design? What can we, as filmmakers, share with you about how our great cities will, or could, look like 10, 20, 50 years from now? Here is a write-up of Marc’s speech, which dives into how film inspires how a building will look and operate, and influences who will use it.

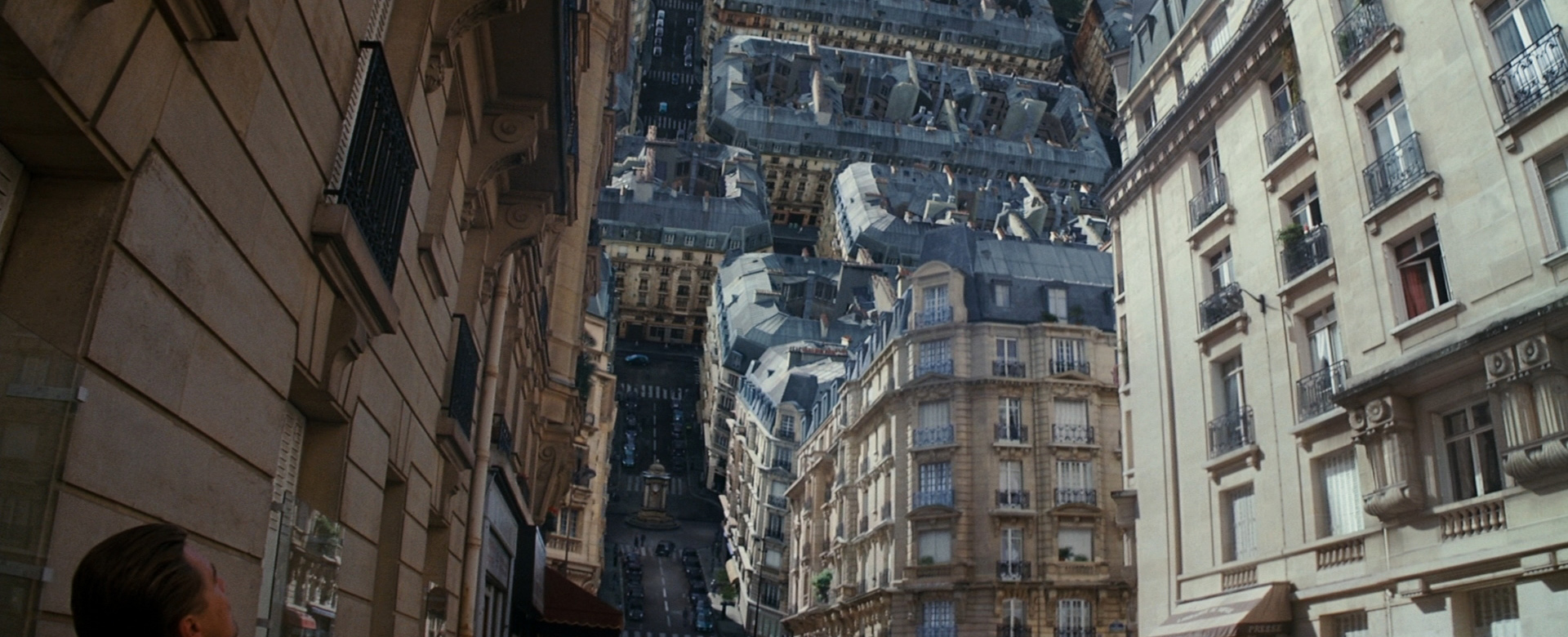

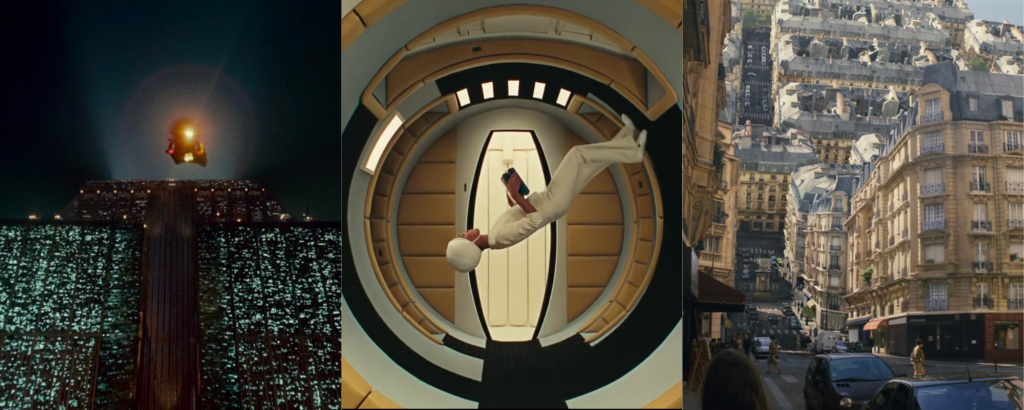

When we think about film, we do still tend to think about the movies, and it doesn’t take much for us to recall those movies which present us with dramatic visions of the future. These landscapes aren’t simply a vehicle to frame a story, they also invite us to imagine the future, challenging our preconceptions about what is possible, what is desirable, what should be protected, and, perhaps, what should be avoided.

The link between Hollywood and architecture is not coincidental; many movie directors and designers began in the ‘real’ world. Joseph Kosinski, the Director behind blockbusters including ‘Oblivion’ and ‘Tron Legacy’, actually received his Master of Architecture degree from Columbia University. He started in the built environment, before making what felt to him like a natural transition to the world of film. Anshuman Prasad, a set designer on films such as ‘Captain America: Winter Soldier’, ‘Maleficent’, and ‘Batman vs Superman’, frst studied architecture at the Manipal Institute of Technology. Tino Schaedler, a digital art director whose reel includes ‘V for Vendetta’, ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ and ‘Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix’ taught architecture at UBC and the Architectural Association.

When asked about the transition from architecture to movie-making, a common theme is one of freedom – freedom of wanting a broader canvas to create on, without the limitations of real-world physics, engineering and red tape. But we don’t need to pack our bags for Hollywood just yet to realise how films can expand our creativity and our architectural urges to communicate a vision of the future that perhaps only exists in our imaginations.

When it comes to architecture, films can still tend to be an afterthought. They are generally commissioned and shot only when a project has been completed; all too often, we use film to report on what has already been decided and achieved, and all too rarely to communicate a future vision.

When we only use film to showcase what exists, our story is limited by what has already happened. As such, the audience is passive, like the movie goer, simply consuming and judging. But when the film comes before the architect’s first etch, it can act as a powerful creative catalyst. We know this is true in the way that movies have inspired real life.

Bar Luce, the café located at the entrance building of Fondazione Prada, Milan, was not only inspired by the Grand Budapest Hotel, but was actually designed by Wes Anderson himself.

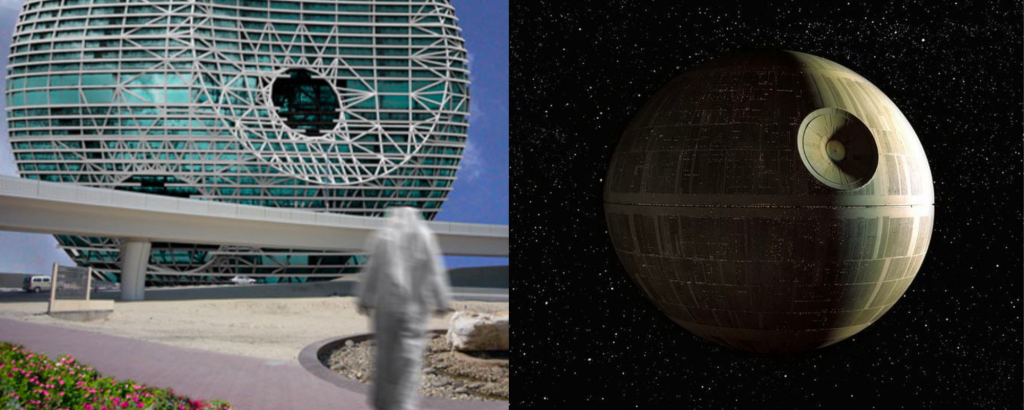

Architect Rem Koolhaas had Star Wars very much in mind when he designed the RAK Convention Center in the United Arab Emirates.

The pyramidal structure and height of the unfinished North Korean Ryugyong Hotel was based on the Ministry of Truth building from Orwell’s ‘1984’.

Now, the point of sharing these examples is not so much to say that buildings and spaces can be inspired by the movies – that much we already know. Rather, these examples should get you to consider that creating a film is the perfect medium to share a vision and to test ideas. When we use film to illustrate the potential of a future building or space, t can invite conversation and collaboration. The audience can become active stakeholders, able to input into how a building can look and operate, able to shape the ‘WHAT’, as well as the ‘HOW’ of a place.

The WHAT, and the HOW, and also the ‘WHY’. Communicating the ‘WHY’ of a building – WHY here, WHY now, WHY like that – is the most powerful argument for commissioning the film before laying the foundations, or even selecting the site. Because film is not just the medium of the visual artist, it is the medium of the storyteller. The ‘WHY’ of a building is what generates our emotional attachment to it, the story is the beating heart that complements the analytical brain. We need emotion and story to make the most pragmatic decisions. If you think about some of the buildings you love, aren’t they infinitely more interesting when we know the backstory? Venice’s Basilica San Marco takes on a new resonance when you learn that it is not simply named after St. Mark, but was built to house his body after it was ‘rescued’ from Muslim controlled Alexandria, Egypt, where it had lain for 7 centuries. ‘The Dancing House’ in Prague takes on more significance when you know the story of the Czech Republic’s transition from communist regime to parliamentary democracy, commemorated by the building’s two-part structure. The Taj Mahal, was commissioned by Shah Jahan to commemorate his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who died in childbirth.

When an architect uses film to tell their Genesis story, before the diggers and cranes move in, they not only get to explain their ‘WHY’ to others, they also invite these stakeholders to emotionally invest in their project. Prospective tenants, investors, the local community, planning and city boards, ESG groups. People whose views and intentions not only matter, but are best known early. Film can expedite and ease these conversations with regulatory, environmental, and commercial stakeholders, acting as a lever to get them bought in way sooner than they normally would, and engaged more powerfully than a drawing or blueprint ever could on their own.

With film comes narrative. We don’t just see the proposed materials, we get to appreciate why the architect wants to build with these specific ones. We don’t just guess what might be influencing the architect, we get to travel back as they narrate the evolution of their inspiration. We don’t just see a curve or a straight line, we get to understand what certain shapes mean to the architect, and crucially why. Just like the movies that we best remember, the ones that challenged opinion, galvanised communities, and triggered real change, the films that tells the story of WHY a building needs to be built also have the power to influence how it will look, how it will operate, who will use it, and possibly even how it will be funded.

Cinema has always provided architects with the impetus. To imagine what the buildings and cities of tomorrow could look like by translating those ideas and visions back into film, we can make the process of creating a new building a more collaborative and emotionally driven experience. One that benefits from more people and better ideas with more engagement, and far greater emotional and financial investment.